The Price of Ramen

Photo by Bethany Johnson

In its tattered leather case, my phone rings. I pick up to hear Kalena’s voice on the other end.

“Can you put my MacBook in my backpack for me? I left it on one of the chairs in the cafe,” she says.

My memory swerves to moments earlier catching sight of him, hands in lap, face thrust forward, staring mindlessly into a laptop screen at the cafe.

“I think he took it,” I reply.

Hours earlier, before Kalena’s call, I was walking down Orchard Street on a breezy Saturday morning past crowds of Lower-East-Siders taking in their weekend the hip Lower-East-Sider way. Striped-shirt, beret-topped ladies brunching at corner cafes and baggy-jean, moppy-haired men skateboarding down sidewalks. Smoking on stoops, boxing in clubs, shopping in alleyways and posing for pictures, the grungy villagers make anyone walking the streets near Bowery feel cool. That is, until I reminded myself I am on my way to work.

In the early 1900s the neighborhood around the Bowery swarmed with drunks, bums and prostitutes. The street, which New Yorkers dubbed “Satan’s Highway” and the “Mile of Hell” and avoided at all costs, now attracts packs of tourists to its edgy hotels that claim their rich history in the neighborhood's past.

Photo by Bethany Johnson

Though it may no longer be the residence of 14,000 homeless people, one cannot avoid their presence in the borough. The city currently faces what Mayor Eric Adams coined a “historic surge” in homeless shelter applicants. On Oct. 10, 2022, city shelters hit an all-time high of 62,174 residents according to the Department of Homeless Services. As Mayor Adams advocates for the opening of more shelters, many neighborhoods push back on having a shelter located on their streets.

By 10 a.m. I arrived at the back entrance of the museum, swinging open one of the chunky glass doors, and began opening up the museum’s bookstore.

I work at the International Center of Photography (ICP), a photography school and museum located at Essex and Delancey Streets in the Lower East Side. My boss, Jim, recently promoted me to “supervisor.” That upgrades my pay an extra $1.75 an hour.

When I got the offer, I impulsively replied, “Oh great, that will buy me…”

I could not think of what an extra $1.75 would afford. The fair trade, single-origin, organic, locally roasted coffee I bought on my way to work cost $7 and lunch would cost at least $15. Since the pandemic and war in Ukraine, purchasing food is all the more expensive. Even the price of canola oil is up by 159% and the average cost of eggs has increased from $1.83 to $2.90, I recall reading in the New York Times that morning.

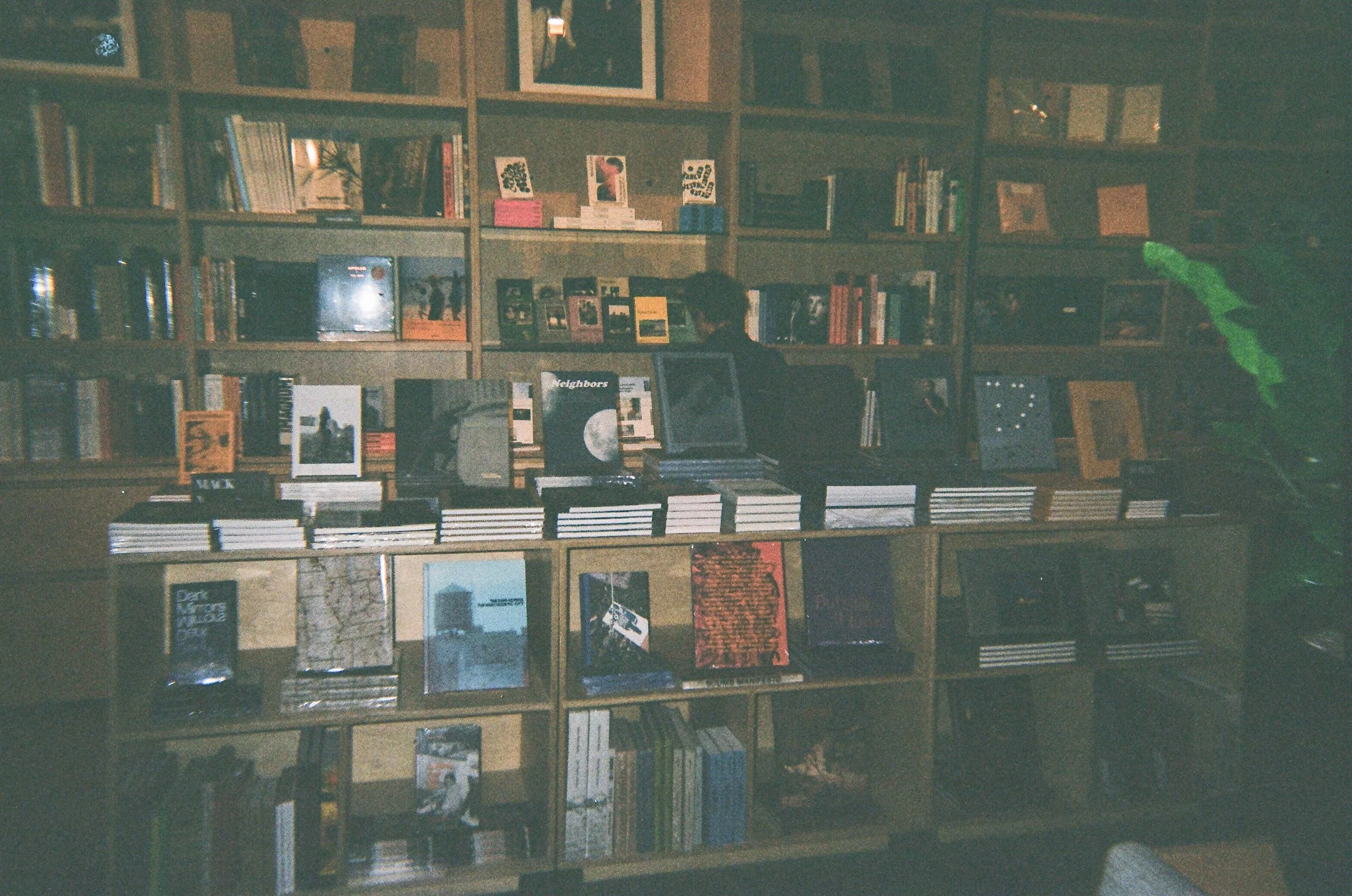

When a visitor enters the International Center of Photography, the museum's narrow walls direct them into the cafe decorated with a glass case of almond, chocolate and plain croissants, blueberry scones and cookies. Continuing their way to admissions, tables of books distract their attention. Looking up, more books crowd the ceiling high shelves: Robert Capa’s war photos, Dawoud Bey’s Harlem street portraits, Hassan Hajjaj’s documentary fashion snapshots and Nan Goldin’s visual diaries among dozens others.

With their classy and flashy Leica, Fujifilm, Sony, Nikon or Canon thrown over their shoulder, strapped around their neck or clutched in their palm, the customer peruses the photobooks wide-eyed. Later, they will undoubtedly leave with a touch of inspiration on their face and possibly a postcard of a Spanish Civil War soldier crashing to his death, a Nicaraguan Revolutionary tossing an explosive or a Gypsy handcuffed in Soviet-invaded-Czechoslovakia.

ICP Bookstore | Photo by Bethany Johnson

At 11 a.m. I checked my phone to see who else Jim scheduled to work. None of my coworkers showed up. I made up my mind to go ahead and open up the museum alone. I unlocked the front doors. The upstairs gallery was under installation for the upcoming exhibit, but the bookstore and cafe were still open and the school would be hosting a zine-making event in the cafe later in the day. I messaged my boss that I will handle the bookstore and cafe on my own for the day. What could go wrong?

At 12 p.m. Kalena slid out of a cab and entered the museum. Her late start to the morning resulted in a missed train at Hollis Station and a last minute impromptu cab ride. She is 20 and wheeling through life.

After helping out in an ICP educational program upstairs, Kalena headed downstairs to greet guests and invite them to take part in the weekend’s zine workshop.

Kalena | Photo by Bethany Johnson

Kalena | Photo by Bethany Johnson

Moments later, a cheery group of families, friends and couples were snipping and clipping away at magazines and postcards, crafting little paper booklets. A boy in a saggy gray sweatshirt and black pocketed pants sat alone on one of the cafe’s benches and gazed with clouded-eyes at the ziners..

Kalena left the table, smiled gently and slightly tilted her head as she addressed him and offered a glass of water and pastry from the cafe. He accepted and a moment later lies down on the booth and shut his eyes.

Kalena recalled the situation, “A parent came over letting us know she was uncomfortable with a guy sleeping looking strung out near her child. ”

Roy, another employee at ICP, stood up from his seat at the workshop table and walked over to the bookstore to message some contacts asking about resources that can help the young, hungry guest.

Zine Workshop | Photo by Bethany Johnson

The visitor’s age remains unknown. He appeared to be between late highschool and early college age. For the sake of the story, I will refer to him as Chris.

Four children dashed past Chris, who was then sauntering around the bookstore. The kids explored the shop as well.

One of the girls snatched a miniature apple red Polaroid camera and asked, “How much?”

“Ninety-nine dollars,” I replied while watching Kalena hand a paper bag packed with granola bars and tangerines to Chris.

Next, she picked out a gift shop sweatshirt, purchased it and gave it to him.

After the workshop Kalena talked to Katarina, another ICP employee, about the day’s turbulence, beginning with her chaotic morning commute, to finding me running the museum by herself, to helping a hungry, jobless youth.

During the conversation, her phone lit up with a message I sent, “It’s near the museum’s closing time.”

That’s when my phone rings, in its tattered leather case, hearing Kalena’s voice on the other end. It felt like the floor lights faded as Kalena’s thin figure came towards me waiting for her in the empty cafe.

“I saw him with a Macbook at the table, and I assumed it was his,” I said as we searched around the room. “He left and now there is no laptop in the cafe.”

She did not say much at the time. Neither of us could believe it.

Weeks later, recounting the moment, Kalena reflected, “The idea of losing it made my heart hurt. Especially after helping someone — it made me not want to help anyone else out afterwards — but I knew that was not the right thing to do.”

The following morning at 10 a.m., Kalena storms through the museum door with her childhood friend, Bri, by her side.

“We are going to find my laptop,” she says.

She pulls out an older laptop of hers and locates her MacBook with the Find My app. Ten minutes later, she heads outside with Bri who ragefully declares how she will handle this senselessness.

I anticipate their return, watching through the glass as people pass by. A man in torn trousers with arms spotted in quarter-sized sores stumbles across the street; two girls in skin tight silky black dresses speed up their pace to avoid any chance of confrontation with him. Hunched over, palm pressed against a graffitied wall, trying not to heave, a girl in knee-high black leather boots lets her friend rub her back as she attempts to pull herself together. A man exits the bodega on the corner with a box of cigarettes.

Photo by Bethany Johnson

I hear Kevin, another coworker of mine, in the backroom office with Kalena on the phone giving him minute-to-minute updates of the MacBook hunt. I take a break from the suspense and head over to the cafe. I inhale the toasty aroma of espresso oozing out of the machine and glance up to see Kalena grinning with the laptop cradled in her arms.

“Where was it? Who had it?” I ask.

“Down the street. He traded it for a bowl of ramen.”

Bethany Johnson is a senior studying Journalism, Culture and Society. She is the Photo Editor at the EST.