Minimalism: Objectively Superior or Subjectively Elusive?

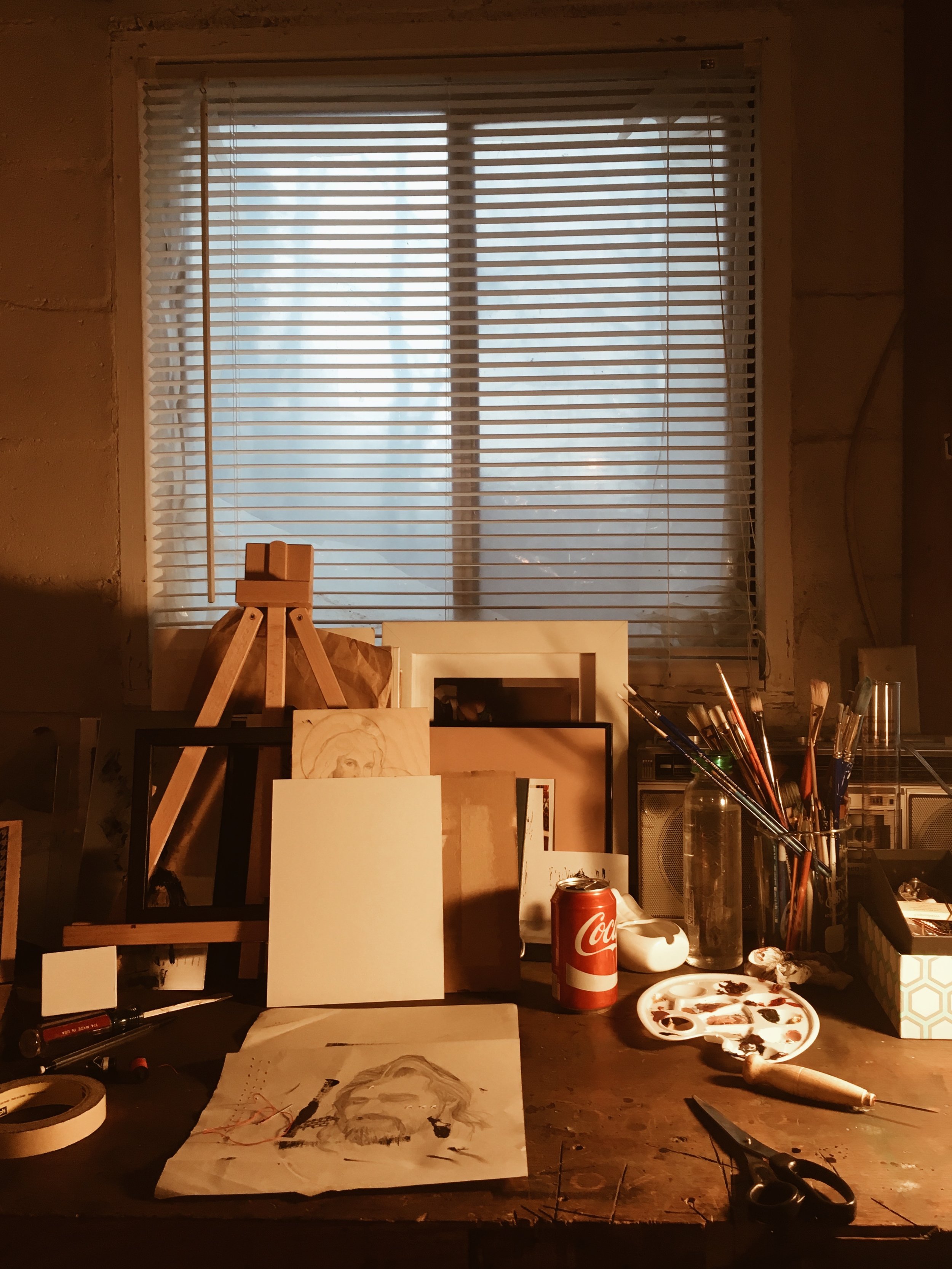

Photo Credit: Abigail Jennings

The opinions reflected in this OpEd are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of staff, faculty and students of The King's College.

I’m now going on three years and 10 moves in New York City. During each move, just when I thought I had downsized, I would find myself tripping over bag upon bag. Where does it all come from, I thought. I don’t need all these kombucha bottles and shoes, really. For a student living in New York, a lot of room is ideal—but the reality is shoe-box-sized apartments. While this can be a good exercise that keeps us from the New Yorker compulsion towards materialism, this usually requires a detachment from the material world—everything from the useful to the sentimental—which is not necessarily healthy.

Modern minimalism rejects any place for materials that remind us about the gravity of our reality--that we are mortal. Abigail Jennings, an artist and King’s alumna now residing in North Carolina, shares her insight into the purpose of still-life pieces of art. In her studies, she found that material objects are “memento mori, serving as reminders of mortality through the use of objects like skulls and perishable items like oysters, fruits, and flowers.” Art is not just about inspiration but also remembrance, solemnity. This principle of art also holds true in our personal lives. We are both spiritual and physical beings, and we must be reminded of this.

On the whole, the minimalist goal is optimization. Considering the effects of possessions is well and good, but without the proper object in mind—the Good life, instead of subjective ideals—one is left both materially and spiritually empty.

Instead of affirming one’s spiritual life, the focus of minimalism is stripped to the efficiency of objects. Material objects are either good because they aid one’s production or quality of life, or they pollute it. Asceticism that rejects materials, especially luxury, is not necessarily better, either. The problem with materialism is not about objects but rather a person’s attitude towards them. It is this disposition of a person that marks their desires—whether they own few things or hundreds, all habits are motivated by their state of mind and indicate the health of their relationship with the world, both physical and spiritual.

Thus, a good life requires training one’s tastes to an objective Truth. On the whole, the minimalist goal is optimization. Considering the effects of possessions is well and good, but without the proper object in mind—the Good life, instead of subjective ideals—one is left both materially and spiritually empty.

Prominent leaders of modern minimalism, like Joshua Fields and Ryan Nicodemus, define minimalism as “a tool to rid yourself of life’s excess in favor of focusing on what’s important—so you can find happiness, fulfillment, and freedom.” The founders of “New Minimalism,” Carey and Kyle, “want to be inspired by [their] spaces, surrounded by beauty, by good design and style.” They believe that “having less junk is the simplest way to achieve that.” Though not all in the minimalist movement deny investing in beautiful things, without a proper end, the goodness of actions are null.

Choosing minimalism as a lifestyle is hollow because it reduces life to one of shallow subjective whims.

The focus on efficiency is short-sighted, then, because it rules out material objects unless they increase efficiency, instead of enriching one’s life, whether by way of the sobering remembrance of death--as memento moris--or the joys of life.

Minimizing is not necessarily bad. But the motive and the end need to be proper. Choosing minimalism as a lifestyle is hollow because it reduces life to one of shallow subjective whims. The Christian tradition believes that man’s desires are disordered; this includes man’s relationship with the material world. The remedy is cultivating and practicing good habits, not merely throwing out the closet. Perhaps Epicurus was right: we should focus on our attitude towards things rather than their quantity. We must orient our lives toward a good, flourishing life--the holistic life God intends us to enjoy.