Honor in the real world

Andrew Schatz is a '10 PPE alumnus.

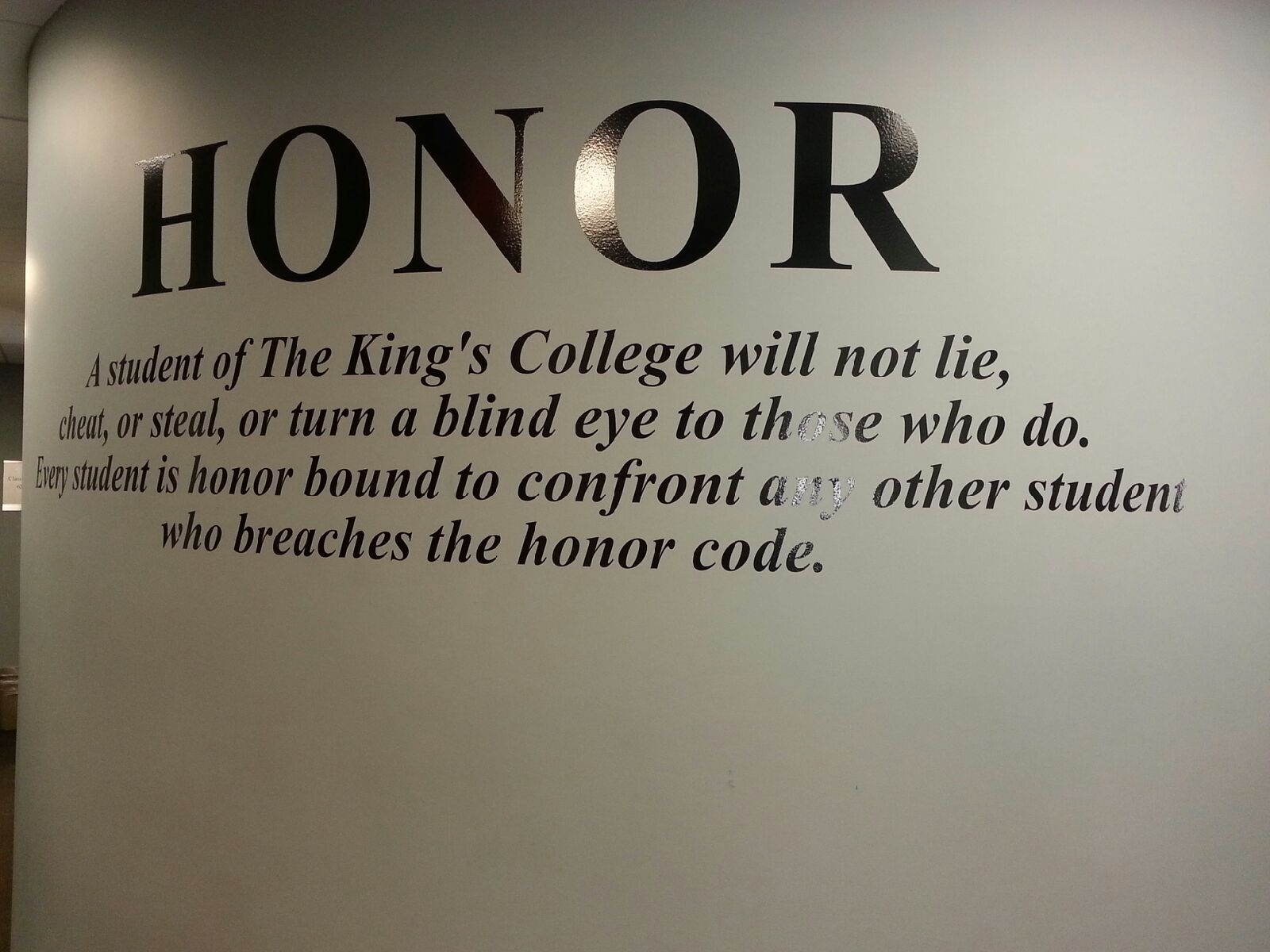

I matriculated into The King’s College in the fall of 2006. Honor, and the code that requires it of every student, was a hot topic. Throughout my time there, it continued to be a frequent point of disagreement and debate. I’m not surprised that the recent conversations I’ve observed on Facebook and in the Empire State Tribune continue many of the same lines of discussion.

Students often questioned the jurisdiction of the code, or whether or not King’s had an obligation to expect lawfulness and moral behavior from students. They questioned the technicalities of implementation and whether or not Matthew 18 is a legitimate roadmap since it only specifically mentions the Church and not “private Christian colleges in 21st century America.” Lastly, they questioned whether or not the school had the right to change the interpretation or verbiage of the code after a student had matriculated.

I have my own opinions on these points, but I fear that dwelling on them for too long distracts us from the purpose of the code. We shouldn’t bicker so much about specifics that we forget what the code is for and its usefulness beyond 52 Broadway.

As simple as Student Development might like to make it sound, the Honor Code is hard. Every day, you’re asked to think not only of your own actions but to encourage your brothers and sisters to conform to the standards that their God, their country and their college require of them. While this can be an incredibly rewarding experience that is beneficial for all parties involved, contemplating the process is daunting.

Instead, you’ll be tempted to spend your four years of college pretending not to listen to certain conversations, inventing imaginary statutes of limitation that happen to expire right before you got up the nerve to confront someone, and waiting anxiously for the day when you can graduate from this odd little college and join the great anarcho-capitalist paradise of “real life” where cops have wooden legs, you never change your socks and little streams of alcohol come trickling down the rocks.

That is not what the Honor Code was set up to prepare you for, because real life is something quite different. As a rather simple example, I’ve spent the three years since graduating from King’s at a company in the financial industry. We are trusted with many billions of dollars to manage on behalf of our clients. People in my industry are known for coming up with creative ways to skirt rules, lie to clients and exploit as-of-yet unregulated territory in legal but unethical ways.

We, too, have an honor code of sorts, and the government calls it whistleblowing. If only it were still as simple as asking a 2- year-old roommate to wait a little longer before going to the bar. Every year, we’re required to peruse federally-mandated PowerPoint documents outlining a code of behavior far more legalistic than any rules at King’s and with far more serious consequences for both the offender and the challenger than the Honor Code as we know it. Not only am I expected to watch for breaches of federal law but even for anything that might be deemed contrary to the fiduciary relationship we have with our clients.

Furthermore, the code at King’s requires simply that you confront the offender; you only have to go to an administrator if you find them unrepentant and the situation requires it. Real life requires that I “tattle” in a way that isn’t expected of any student bound by the Honor Code.

If you think of real life as something that starts after you take off your cap and gown, it won’t be much of a paradise. But if you think of your life now as real and the decisions you make in college as important for the growth of moral character, you’ll be able to handle stricter honor codes as well as greater freedom.

The rules aren’t part of the Honor Code itself, but keeping the rules is a matter of honor that you commit yourself to when you join the community. The most important thing is to remember your principles, those of your community and those of your religion. All three need to be in line. If you find yourself quibbling about jurisdictions and technicalities then you may find yourself more on the side of legalism than Christian freedom after all.