Train Ride to Nowhere: Facing Homelessness in NYC After Aging Out of the Foster Care System

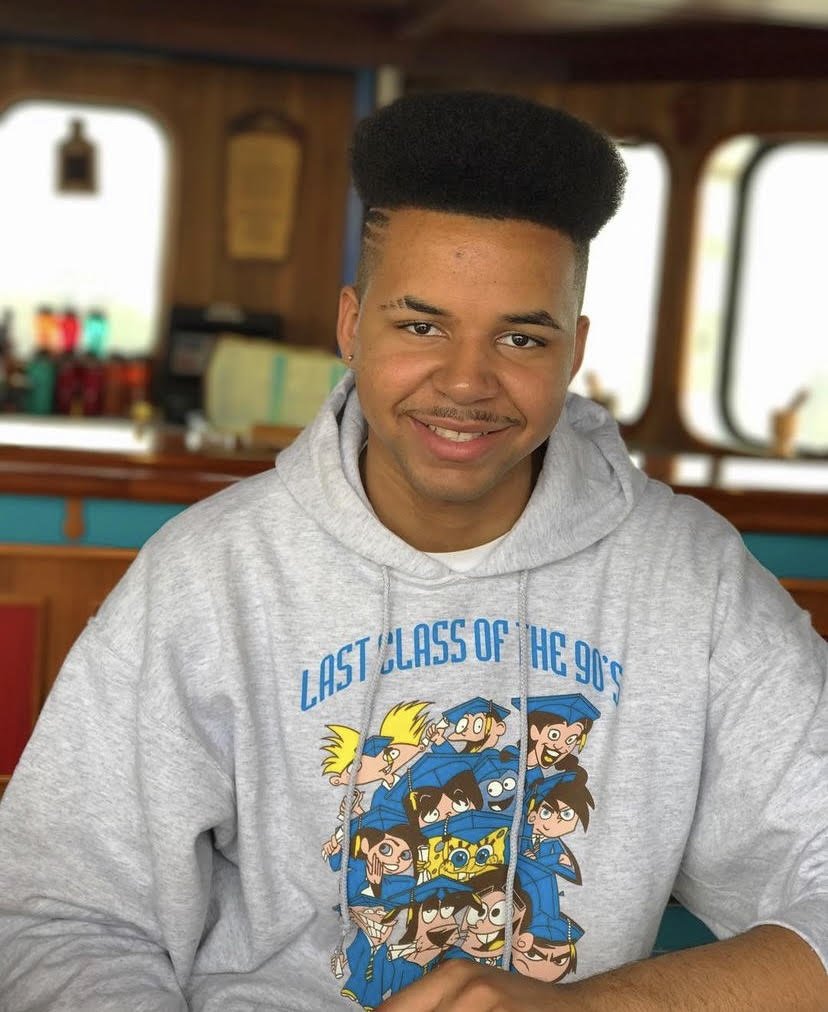

Larry Malcolm Smith leads a group at The Forgotten Children’s Youth March. | Photo courtesy of Larry Malcolm Smith.

He stuffed everything he owned into the garbage bags he had been living out of for years. His past few birthdays, Thanksgivings, Christmases and summers had all been spent within the cinderblock walls of his dorm room in Woodlands Residence Hall — not by choice.

The 2020 spring semester was just beginning. Most students were settling into their dorm rooms on SUNY College at Old Westbury’s campus in Long Island, but Larry Malcolm Smith was getting ready to leave.

With $20 in his pocket and garbage bags in tow, Smith train-hopped to Forestdale Inc. in Flushing, the foster care agency that he aged out of when he turned 21.

The caseworker handed him a $2.75 MetroCard pass. The yellow and blue ticket would buy him a one-way ride on a city bus or subway.

“They were like, ‘You're leaving,’” Smith said.

“Are you serious?” Smith asked.

“You were in school, and you should have made school work,” Smith said the caseworker told him.

“I felt very discouraged because that's a scary feeling to tell somebody that they have to go somewhere, when they don't have nowhere to go,” Smith said.

But Smith is just one of many foster care youth who age out of the New York City foster care system and become homeless not even a year later.

Smith took the one-way trip MetroCard from his caseworker, walked to the Forest Hills-71st Avenue station on Queens Boulevard and boarded the E-train.

For five hours the lull of the subway cart rocked his tired soul to sleep.

He rode the line front to back before getting off at 42 St-Bryant Park Station. The cold park bench was the closest thing he could find to a bed and his coat became the only barrier between his body and the biting winter wind.

With no money and an incomplete college education, Smith spent eight months on New York City streets during the height of the pandemic.

In New York City alone, around 1,000 youth age out of the foster care system every year. Young adults in foster care can choose to be discharged at age 18, and at age 21 they age out of the system according to the New York City Administration for Children’s Services.

Aging Out to Homelessness

In 2015 in New York City, over 20% of youth who exited foster care between the ages of 13 and 18 entered either a Single Adult Department of Homeless Services or Family with Children Department of Homeless Services shelter within six years of their exit, and 53% of respondents said they stayed overnight in jail or a juvenile detention facility according to a study by the Center for Innovation through Data Intelligence.

Foster youth experience homelessness at disproportionate rates. Nationally, nearly 1/3 of young people experiencing homelessness had been in foster care, according to a report by Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Youths are aging out of the foster care system and becoming homeless because the child welfare system is as bureaucratic as any other system, said Stephen Metraux, associate professor at the University of Delaware where he researches homelessness and housing.

“A kid might be deemed an adult at the age of 18 by the legal definition, but that does not mean they are going to be able to successfully provide for themselves without adequate support and resources,” Metraux said.

“We have this better expectation for the most sidelined people in our society to be stable as an adult,” said Sedonmai Agosa, founder of ClearPath, a NYC based nonprofit that helps homeless youth.

Safety nets exist to prevent youth from aging out of the system homeless or from becoming homeless within a few years of aging out, but the safety nets don’t always work.

Inaccessible resources and a lack of guidance and support from foster agencies are issues within child welfare system that allow foster youth to experience homelessness at disproportionate rates.

The safety nets failed Smith who spent his whole life in the system and is now a youth public activist and advocate for youth in the Child Welfare System.

Early Life in Queens

Smith was two-years-old when the courts terminated his mother’s maternal rights and his father was unable to take care of him.

Ventura Armstrong began fostering the boy. He was adopted by his sixth birthday.

“I loved her and she treated me so well,” Smith said. “She taught me etiquette. She taught me everything that I needed to know, and to never ever give up on myself and to always stay strong.”

Armstrong inspired Smith’s early activism.

She was from Montego Bay in Queens and made a “poppin’” Jamaican-style Arnold Palmer.

The two would set up a neighborhood lemonade stand to sell the drink.

But while Armstrong was in the kitchen crafting the sweet lemonade and tea mixture, 6-year-old Smith was handing out cups for free.

“You have me making all this Kool-Aid and this Arnold Palmer and you're not selling the cups,” Smith mimicked Ventura’s scolding.

“How we gonna make more Kool-Aid?” she asked.

But he kept handing out the cups for free.

“I was very hard-headed,” Smith said.

Smith said he remembers telling Armstong, “I just want to help somebody who isn't able to help themselves.”

“You have a big mouth,” Armstrong said. “But your mouth and the community, when they come together you will see a change that you have never seen before.”

Smith’s activism began.

Armstrong took Smith to his first protest when he was eight, and he hasn’t stopped advocating since. Under the pseudonym IAMQUEENS, Smith organizes protests and marches to advocate for foster youth.

Smith said he always wanted a bigger brother or a father figure in his life to stand up for him, and activism allows him to be that figure for other people. Smith advocates for foster care youth today because he experienced neglect and mental and physical abuse growing up in the system after his adoptive mother died when he was 11.

Larry Malcolm Smith tells people about his experiences growing up in the foster care system at The Forgotten Children’s Youth March. | Photo courtesy of Smith.

Larry Malcolm Smith advocating for foster care youth. | Photo courtesy of Smith.

He spent the next 10 years moving around New York City, stuffing his belongings into garbage bags as he moved from house to house.

Smith’s pre-teen and teenage years were a blur of 23 homes: foster homes, group homes, children centers and covenant homes.

“I was being ripped away from not even my family but being ripped away from a stranger's home,” Smith said. “I was never adopted again. I was used as a check. I was exploited. I wasn't the worst kid at all, but I would run away and do things that I shouldn't be doing as a child, but it was because I wasn't safe.”

Smith said he was sexually assaulted and sex trafficked and often went to bed hungry.

At one home, Smith ate uncooked ramen noodles and watermelon or Pop-Tarts and TV dinners while his foster parent’s biological children ate home-cooked meals, he said.

“We have to figure out a way to change this system and figure out something that doesn't just work for some but works for all of us,” Smith said. “Our humanity must be recognized.”

Trauma attributes to why child welfare users disproportionately face homelessness, incarceration, unemployment, arrest, incomplete education and early pregnancy.

“These kids, they experience just extraordinary trauma, and so it's an uphill battle under the best of circumstances,” said Gabriel Brodbar, former founding Director of the Office of Housing Policy and Development at the New York City Administration for Children’s Services.

But Smith managed to graduate high school and was accepted into SUNY College at Old Westbury. He started his freshman year in the fall of 2017 as a criminology major.

He joined the Student Government Association and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and became the president of the Black Student Union.

The young activist was always finding ways to advocate for change on campus.

During his junior year in the fall of 2019, he organized a student walk-out to protest mold growing in residence hall showers, ceiling tiles, mattresses and contaminating some students' clothes. Smith was using his asthma machine in the morning, at lunch and dinner because the mold was worsening his symptoms. Smith was also struggling with his mental health.

Smith posted on Twitter about taking his own life. Smith said the tweet was misconstrued and believed to be a threat to students. The subject of the social media post was deemed by University Police to be a terroristic threat under New York State’s penal code, and after the post was investigated, an arrest was made, according to an email sent from Calvin O. Butts, III to the SUNY Old Westbury student body.

Smith was arrested in December 2019 and charged with a Class D Felony for making a terroristic threat. He was incarcerated for 28 days in the Nassau County Correctional Center. The charges have since been dropped by the Nassau County Criminal Courthouse.

| Photo courtesy of Smith.

At SUNY Old Westbury, if students post something on social media that could be a threat to either to themselves or other students, the post is sent to the University Police Department for review and to decide if further investigation is necessary, said Michael Kinane, Vice President for Communications and College Relations at SUNY Old Westbury.

“It's really just done because we want to make sure our community members are safe,” Kinane said. “If somebody's going to hurt themselves and we can help them, we want to do that too.”

If the University Police, who are law enforcement officers trained alongside the state troopers of the New York State Police Academy, find that a college rule, local, state or federal law was broken, that student is either arrested or introduced into the student conduct process through which the student has a hearing to decide the appropriate course of action.

On Jan. 22, 2020 Smith received a letter, a day after his student conduct hearing, from the college’s Conduct Board charging him for “Failure to Abide by Federal, State and/ or Local Laws” and “Threatening or Abusive Behavior.”

The letter informed him that he was expelled. The news of the expulsion came three months after his 21st birthday, meaning he would no longer receive support from the foster care system.

“I aged out with nothing,” Smith said. “School was my biggest lifeline as a foster child.”

Smith couch-surfed and slept in people's cars, parks or subway trains.

“Former foster care youth might not have a home base but they still need a place they can turn to for support even once they have aged out,” said Metraux. “There is a need for more transitional services and more kinds of extended services to provide a softer landing into adulthood,” he said.

Searching for Support

Experts in the child welfare field say that providing youth with not only a place to live but also the wraparound services, such as education support, mental support and guidance for things such as how to access healthcare and prepare healthy meals is the key to successfully helping youth to age out of the foster care system.

“Here's a population that is in need of housing and services,” Brodbar said. “There are proven models that work. And the solution is cost-effective. It's cheaper to prevent people from becoming homeless than it is to allow them to become homeless.”

Currently, The New York City Administration for Children's Services (ACS), a governmental agency that provides services to New York City children in foster care, has systems and resources in place to prevent youth from aging out of the system homeless.

But continuous state budget cuts to child welfare programs and multiple barriers to accessing resources mean the systems in place are not as effective as they could be. In New York City in 2019, 21.38% of the total youth who aged out of the foster care system entered the shelter system within one year of being discharged from foster care, according to data from ACS.

The government agency connects youth to a number of housing options, including public housing, Section 8 vouchers and City FHEPS vouchers. But, if the voucher application is even approved, it is then up to the recipient of the voucher to find a landlord that's willing to accept it.

“While a landlord is not allowed to refuse a tenant simply because they have a Section 8 voucher, it happens all the time,” Brodbar said.

ACS agencies hold trial and final discharge conferences before youth exit foster care to confirm where a youth will be living, prior to any discharge being finalized. If a youth does not have stable housing identified, the discharge does not proceed, an ACS spokesperson said. And ACS’s Housing Academy Collaborative prepares youth to maintain long-term New York City Housing Authority public housing or supportive housing when they transition out of foster care.

The agency also provides youth with referrals to educational sites, mental health services, programs through the Human Resources Administration and assists in obtaining vital records. The Fair Futures program provides all youth in care who are 16 and above with dedicated coaches, as well as tutors and housing specialists.

But some agencies under ACS are not able to effectively connect foster youth with the available resources because of a lack of case workers and funding, said Agosa, whose nonprofit organization, ClearPath, provides teenagers phasing out of the foster care system, runaways and youth experiencing homelessness with direct access to a free directory that helps them find programs that are designed to elevate them out of potential homelessness.

Barriers to Access

According to the New York City Independent Budget Office, “Governor Cuomo’s 2018 Executive Budget included a proposal — which was ultimately enacted — that cut ACS’s portion of the statewide Foster Care Block Grant by approximately $44 million per year.”

On top of budget cuts, an ongoing surge in investigations and court cases have repeatedly driven average caseloads above 15, 16, and even 17 families per caseworker in the past two years, and in some offices, experienced workers carry loads well above 20 families at a time, according to a 2018 report by the Center for New York City Affairs. The Child Welfare League of America recommends caseloads of between 12 and 15 children per caseworker.

“Even the best people in those positions with the best intentions, their problem, in most cases, is they are overworked,” Agosa said.

Hard-to-access resources, overworked staff and budget cuts are just a few of the issues that cause foster care youth to either age out of the system homeless or become homeless shortly after aging out.

ACS has implemented a number of strategies to help youth who have left care, knowing that their circumstances can change and they may face new challenges after leaving. While all federal and state foster care funding ends at age 21, in certain situations, ACS extends foster care beyond the age of 21 to ensure youth have stable housing and needed support.

Currently, there are 208 youth over the age of 21 living in a foster home or residential placement, fully funded by ACS.

Escaping Homelessness

Smith finished his shift at Chipotle on Flatbush Avenue in Brooklyn and rushed back to The Christopher, a shelter in Manhattan that he moved into in May 2021 after months of homelessness.

He was just in time for the 10’ o'clock curfew. He is not allowed to have guests. He has four roommates. He sleeps on a bunk bed.

“It's like jail,” Smith said. “You're always supervised. You don't feel safe with your stuff. Your stuff is never locked up.”

Smith knew this wasn’t it for him.

Between his Chipotle shifts he went to the Muhlenberg Library in Chelsea to fill out college applications. Even though he was expelled from SUNY Old Westbury, he still wanted to complete his degree.

On Oct. 22, 2021, at 4:08 p.m., his phone dinged.

The notification in his inbox was from the President of John Jay College. The subject line read: “Congratulations from John Jay College.”

Smith was accepted into the Spring 2022 transfer class at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice to study criminology. This acceptance letter was the first of many.

Smith stands in front of a sign at his new university. | Photo courtesy of Smith.

On Dec. 15, 2021, Smith was accepted into North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University as a transfer student for the Spring of 2022 to study African American Studies. He moved into a dorm and started his spring semester in January.

“I didn’t think none of this would ever be possible,” Smith said. “I feel like I’m proud of myself and it's a second chance at life. It's a blessing, and I'm ready to take it from here.”

Smith plans to use his education to continue to advocate for foster care youth. He believes that children need to be raised and represented by parents who love them and not by disconnected government officials.

“I'm 23 years old now, and I'm telling people, ‘I wish I was adopted, I wish I was adopted.’ No, it's not that I wish I was adopted, I needed to be adopted, I needed to have a home, I needed to be loved, I needed to be nurtured, I needed to be cared on,” Smith said. “After a while you get older, it's like, your trauma, it follows you.”

With the spring semester at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University coming to an end, Smith does not know where he will live over the summer. It’s too expensive to stay in his dorm. He still packs his belongings into garbage bags and homelessness is still a threat.